Alex Wisser

Category: Uncategorized

October 18, 2023

The Capertee Weaving Water Project

by Alex Wisser

This project has been written about extensively at ksca.land

In 2018 while hanging out in a paddock near the river in the Capertee Valley, planting trees, I met Jen Quealy. She was working for Nepean Health and within the first five minutes of our conversation, she mentioned that she was looking for a community group to apply for a $50,000 drought related well being grant that her organisation was charged with dispensing. I quickly introduced her to the local community leaders Kerrie Cooke and and Terry Wallace and the Resilient Farmer’s Project was born. The Capertee Weaving Water Project was to be a component part of this larger, more pragmatic project that would bring the farming community of Capertee together to consider a whole of catchment approach to restoring the hydrological function of the land. You can read more about it here

The Capertee Weaving Water project was a series of artistic engagements lead by artist Leanne Thompson who had recently purchased a property in the Valley. This is the final work, a collective woven sculpture made by the community to “embellesh” the contour of a local hillside. Contours are an essential element in Natural Sequence Farming and are used to track and influencing how water moves across a landscape. The intention had been to use the art as a way of creating dialogue within the community about the shared hydrological environment in which they lived, but the project was disrupted by both COVID and the 2019 bushfires, and this dialogical dimension was diminished. The project did go ahead, through a mix of in person and online engagements and I was able to involve myself in something of the dynamic response of the community to the bushfires, I view this as a partial failing of the project. The project also struggled (and failed) to engage directly with any of the more conservative elements of the community

Nevertheless, the project was completed with this beautiful sculpture and an amazing Aboriginal water ceremony at its culmination. I mention the failings of this project, not to denigrate its real achievement, but because it was these negative aspects that yielded for me the most fascination. I have noticed with socially engaged art that there is a moment of immersion when the high ideal of the project in its conception meets the base material reality into which it is meant to be made manifest and the generally disintegrative effect this has on the former. Things fall apart, the centre never holds and all the fine clarity in which the idea was conceived gives way to the mixed confusion of obscure, inarticulate resistances, contradictions and refusals with which the real world meets the idea. While it often feels like the disintegration is absolute, and the intention of the work is lost to the contingencies and compromises of what is possible, it is important to remember that this is the nature of the exchange. While what remains, after the deluge feels like a faint and superficial trace of the original idea, and all the clearly articulated goals and outcomes intended in the original project, seems to be a kind of rhetoric, the residue of words and promises. But this residue is everything and I must remind myself not to forsake it. This is how the reality is born into the world, and while it will never be available to measurement or direct confirmation, there it is, changing the reality in effects that will unfold over decades if not longer. All of the conversations that this impossible folly has engendered, all of the conflicts it catalysed out of the original suppressed contradictions of the social reality it disturbed. These are realities also, these are facts that beget further facts, that change the course of thought and with it behaviour and activity. If it enters into the concourse of a great river in which its contribution cannot be calculated, who cares. It enters and contributes nonetheless. I am happy with that.

September 8, 2023

An Artist, a Farmer and a Scientist Walk in to a Bar Newspaper:

by Alex Wisser

This post was originally published July 22, 2021 on ksca.land

The conclusion to this amazing project was this beautiful object here, a 60 page newspaper documenting the journey of this incredible project. I am completely grateful and impressed by this amazing group of people. I highly recommend a read

August 24, 2023

THE EARTH YOU CANNOT KNOW

by Alex Wisser

This post was originally published on ksca.land on August 2, 2020

Alex Wisser takes you on a journey into the earth. In his own words, it was a journey that progressed at a rate of several centimetres per day, as he made his way into the ground, hand digging a three metre deep hole that took him through an involved contemplation of the meaning of the earth and the many facets of our relationship to it.

Videography by Justin Hewitson.

This project was supported by ‘An artist, a farmer & a scientist walk into a bar…’ a major arts initiative in rural Australia in 2018-2020. Involving 9 artists, it was a series of collaborations exploring regenerative farming, soil health, Aboriginal country, solar energy, carbon sequestration and wild foods. It was led by Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation (KSCA), working in partnership with Cementa Inc., The Living Classroom and Starfish Initiatives, and was funded by the NSW Government through Create NSW. You can find out more at https://www.ksca.land/alex-wisser-project

August 17, 2023

IF THE EARTH COULD SPEAK, WHAT WOULD IT SAY?

by Alex Wisser

This post was originally published August 22, 2019 on ksca.land

‘The Hole for The Living Classroom’ has gifted us many puns, and here’s another – it turns out Alex’s existential ambitions go deep, very, very deep. At Groundswell he will conclude his ‘hole’ project with a performance called ‘Earth Oracle’. He will spend 48 hours within the hole, drinking only water and sleeping under the open sky. The public are invited to pose questions to the earth and on the morning of Saturday 7th September he will respond to these questions from within the hole. He’ll emerge later that day, and will be in conversation with MC Adam Blakester about the project on the main stage. You can read an article about it that was recently published in the Inverell Times.

What would you ask the Earth Oracle?

See below for some hole digging action to get you thinking, courtesy of Justin Hewitson.

August 14, 2023

The Hole is Whole

by Alex Wisser

This post was originally published on ksca.land

Its a complete hole. I’ve finished. Its done, finalised. We’ve come to the end. I’ve taken the last photos and video, packed up the car and am ready to drive home. My job is done… I seem to be trying to convince myself of something.

This was a strange, short stretch of time in which I travelled up to Bingara to complete the hole, which I had left unfinished after running out of time on the previous residency. As I left the unfinished hole, I measured my progress and concluded it needed another 60cm to reach the 3 metre depth I had committed to and so I thought I could kick that out easily in 3 days. I had given myself four days to include an excursion to Armidale to present at the grounding story conference on the Artist Farmer Scientist project, along with some of the KSCA gang. This, and a particularly full plate of real world problems worried me as I travelled up to Bingara and settled in for the work. A hundred pressing urgencies, worldly obligations and commitments swirled around me in an incessant stream of anxiety and demand, as I tried to insulate this little patch of time to make art. I know its only digging a hole to many people, but to me it is making art and for that the world needs to recede – which it didn’t seem to want to do.

Needless to say, this residency has had a pressurized feeling. This was only compounded by the fact that I soon discovered that I had farther to dig than I had thought, making my goal of three days uncertain. This, in turn, affected my process, which is usually not end oriented but proceeds by the slow, unrelenting rhythm of my body as I dig, setting pace to the index of physical exhaustion and the variable nature of the soil as it resists and yields to the work I apply.

I now had a deadline and I had to push myself to meet it. Luckily, the soil loosened up somewhat and I was digging faster than I had before. I still had to work overtime a couple days and it definitely affected my thinking, with far more obsessing over the instrumental concern for meeting my goal in time and far less of the dreaming that occurs when the body is set into its automatic motion and the mind drifts in the atmosphere of physical exertion to places it often cannot reach while sedentary. In this there was another tension in the sense that this was therefor a reduction of the work, a diminution of the experience into something merely pragmatic.

Perhaps.

Now that I am out of the hole, in the burning glare of the sun, with smoke from the bush fire in the air (three days ago it was a dust storm), the rivers drying up, the politicians ignoring the calamity and the entire swarm of concerns I had eluded three days ago returned in their more furious form – It is only now that I realize that the work had been not been diminished. Perhaps I just need to dig a little deeper.

August 12, 2023

Into the hole

by Alex Wisser

This post was originally published at ksca.land

So here I am on day 10 and feeling less cranky about things not going the way I planned them, and also feeling a little pleased with myself about the progress I have made. I am in over 1.5 meters which is just up to my shoulder. The going has been both slower and faster than last time, which has pretty much evened out the score. The slower going is a direct result of my clever idea to make the hole bigger. This one will be 2 x 2 meters, while the hole in Hill End was 1.5 x 1.5. I thought this would increase it by a third, but on actually doing the math, it nearly doubles it. I have compensated by wetting the clay at the end of every day, letting it soak in through the night and this has allowed me to keep pace with my planned schedule. Still, I will not finish the hole this trip. After the original 3 days and an additional 11 days of this trip, I will still need to return to dig for another 5 days to get it to the depth that I intend it.

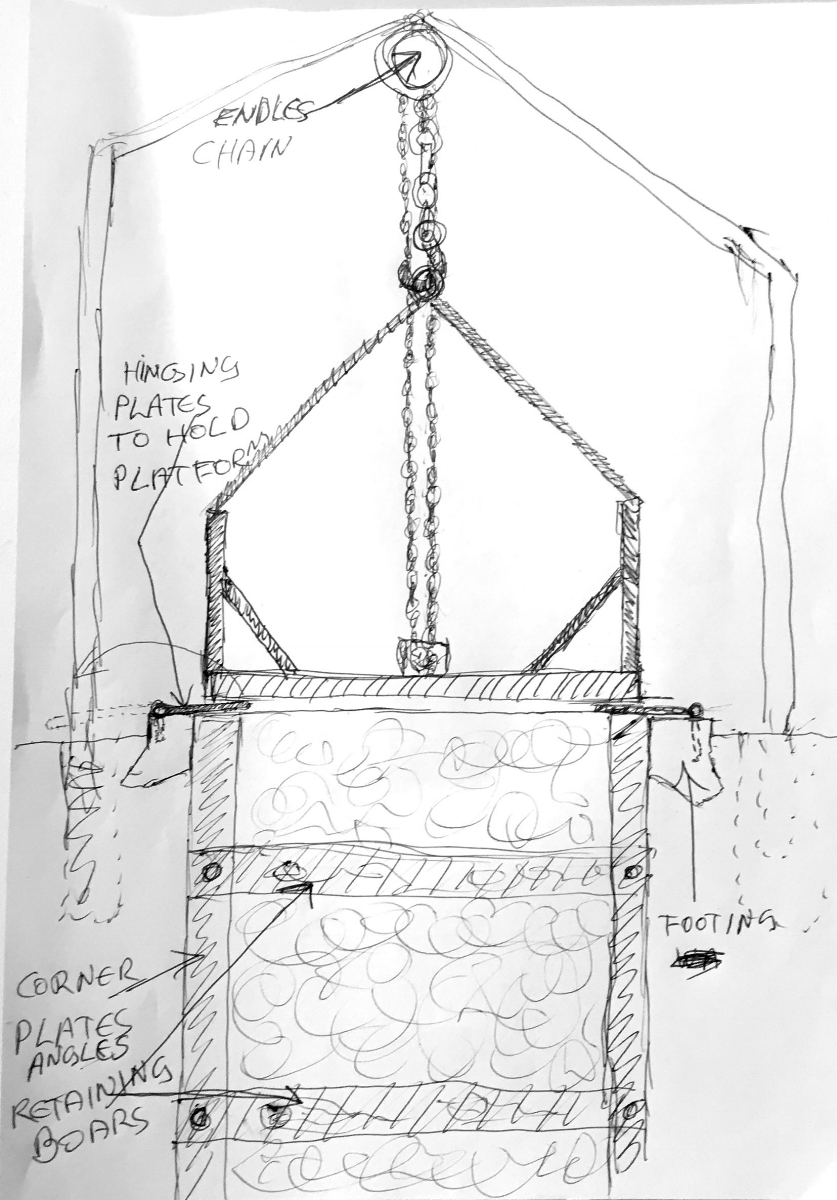

But I don’t want to talk about that. Rather, I wanted to talk about ingress and egress. Or for the layman, not familiar with the nomenclature of holes, I’m talking about how you get in and out of a hole. This is perhaps the most pressing issue facing the project as a permanent hole. How are people going to get in and out in a safe and commodious manner?

Fortunately, my first residency happened to coincide with the visit from a group of architects to The Living Classroom to consult on another project. Rick happened to mention my project and to my surprise, the architects were quite taken by it. They promptly dropped whatever they were officially working on and we embarked on an excited conversation about how to reinforce the hole so that the soil profile would still be visible, how to cover it and drain water from around it, and how you might effect safe and convenient egress and ingress for school children and pensioners alike. While I was a little flattered by the excitement that my humble hole seemed to illicit from the architects, it was also a little distressing as we discussed possible solutions to the last problem. We considered either a ramp or a staircase, but either of which would require an excavation either equal to or greater than the hole itself, and after considering access and oh&s, the price of building either was intimidating.

I was beginning to panic at the thought that the entrance to the hole would be a larger project than the hole itself, when a quiet voice from my left raised the following suggestion. “Why don’t you put in a gantry floor?” A what? A gantry floor is a platform floor that raises and lowers on a pully system, not unlike that which lifts a garage door. It’s completely manual, with the floor raised and lowered by means of a loop of chain. It’s slow moving, but absolutely doable. It’s wheelchair accessible! And the best bit of it is that when you are done, you bring the floor up to the top and it seals the hole so that neither water nor weather, kids nor cats can get into it.

Turns out that the voice to my left belonged to local artist Tony Gomez, to whom I am infinitely grateful. In one fell swoop, his idea solved every problem I faced, including the fact that it would cost a small fraction of all the other options on the table. Leave it to a goddamn artist to come up with a single elegant solution to an entire complex of problems.

August 11, 2023

There is no time in a hole, I have no idea what day it is

by Alex Wisser

This post was originally published on ksca.land

Do you like my fancy title? I put it up there to express something of the complete schedule scramble my entire project has become. I think it might be day eight when I write this and its 3:00am. I have been so exhausted from digging that I haven’t been able to even approach catching up with my social media obligations. I suspect most of this blog is going to go up after I get home. Just to confuse things further, I will spend this post on a prequel to the hole, a little train of thought that occurred to me while I was still at home, waiting for the residency to begin but never got around to because… I was busy. I can’t remember.

As I mentioned in the last post, my original attempt to dig the hole ended in sickness, failure and general catastrophe. I was forced to return home in defeat, to lick my wounds and consider my worth as a human being and an artist. If this sounds melodramatic, it is. Its 3am and I feel I can say whatever I like on the internet and no one will judge me for it.

I spent the intervening months writing grant applications, and making little scraps of money to keep myself and family alive. I don’t want to complain about my life because I like it for the most part, but the postponed work was something that consistently occurred to me. Perhaps this is what became of that youthful experience of the nagging existential need to create stuff because my identity was constructed around the fact that I identified as a person who creates stuff. I don’t know, but it did take me down a particular garden path.

One of the projects occupying me at the time was the house that Georgie and I now own in Kandos. Its a lovely little house that we were able to get up to livable scratch with a bit of paint and floorboard sanding, but the land it sat on was a sad affair, covered in long suffering kikuyu grass and having only one tree on it. We have, over the last two years planted many trees and are slowly working our way around to converting most of it into a food forest of sorts. The property is on a hill and so most of it is sloping, meaning that there are few places to comfortably drink fluids, eat foods and talk talk. I conceived of putting in what I liked to call a sunken courtyard, cut into the hillside behind our house with a large desiduous tree overhanging to shade it in summer, creating a ‘micro-climate’ in which life forms heretofore unknown in Kandos could thrive and amongst which we would gather to drink refreshing beverages and renew our friendships in perpetuity.

To this end, I contacted a fella with a bobcat and got a quote on what it would cost me to get the job done in a day or two. It wasn’t much. It was more than I could afford at the moment but it was definitely doable if I got some jobs and did some work and collected some money up. I can see myself sitting under that large tree, in the shelter of its shade, enjoying my microclimate and my friends and the veritable rain forest of green and living things that would come to occupy my utopia. The idea that I could get the majority of the work done in two days was impressive. I’d have to get a table and some chairs and yes, the whole growing a tree thing would take two to three decades but its a dream, I was going to have made into a reality in two short days.

As I thought about myself in my socially conducive micro-climate, my delight was insidiously overcome by a depressing thought. One achieved, I would perhaps enjoy my sunken courtyard occasionally, but really, the thrill of its achievement would last for only a short time before it would sink into the reality that is the background to all my dreams and, being the creature that I am, I would quickly acquire another dream that I would then pursue with all of the ardor that I had invested in this now forgotten conquest.

This thought, combined with my unfulfilled need to dig a hole and I thought naw… I’ll dig it out myself. And so I have slowly, over the last several months been removing bits and pieces of the small hill we live on and relocating them to another part of the hill up higher, creating another flat area where we might one day build Georgie a castle or put in a basketball court for Emma. Who knows! As I have been digging out that hill, I reflect on how we live most of our lives within a project, with a goal somewhere over the hill at which we aim and then work towards. Even getting through a day of work can be like this. My thought is that if this space of project-ion is where our being takes place, then perhaps we should spend more time within it, and less time hurrying to get to the end of the process, only to find that we need to invent another project in order to get us along the next lap into the future.

This adventure recalled for me the first exhibition we ever hosted at INDEX. Art Space, the ARI space that Georgie and I both lived in and tended for the three years prior to our move to Kandos. The show was called “Live in Your Art” by Margaret Roberts and it reflected on the fact that we were living in an art space, thus superimposing two fundamentally different kinds of space on top of one another, and in doing so, fusing them. This exhibition came to my mind as I dug out the side of the hill behind my house and worried about not making art. As I did so, Georgie labored away building the garden in the front yard through a method of her own devising, which I had come to jokingly call Garden Povera for her use of recycled concrete to create terraces and pathways and her use of bedheads and other tip scavenged oddities as trellases and garden ornaments. All around me, the weeds in the back yard had grown to luxurious heights, a method of building soil recommended to us through our work with KSCA. What was I worried about, I was living in my art, as Margaret Roberts has so presciently pointed out those many years before.

August 2, 2023

STARTING ON DAY 3

by Alex Wisser

The next several posts are directly taken from the KSCA Blog relating to my AFS project. Sorry about the image quality

For those who haven’t been following the project “An Artist A Farmer and a Scientist walk into a bar…”, I am participating by repeating a work I did in 2014 at Hill End, “A Hole for Hill End”, in which I dug a hole for a number of ironic and non ironic reasons in the historic gold mining town Hill End. You can read about it here, because I blogged about it, which means that I won’t have to blog about it here.

Anyway, that’s the past and this is the present, and in the present I am repeating what I did in the past, with modifications. That’s the way things go. The idea to repurpose the work for the current project came from the director of our partner organisation The Living Classroom, Rick Hutton, who suggested KSCA might produce a permanent public artwork for The Living Classroom as a part of AFS. I’m not a fan of public artwork (which you can read about here) and was uneasy at the prospect. I eventually came around to the idea of digging the hole. The original hole was ephemeral, and I filled it in after completing it but this time I proposed to make it permanent. My immediate rationale was that it would be an art work that wouldn’t result in a work of art, but instead would produce a classroom. It occurred to me that this was just what The Living Classroom needed. As a facility dedicated to disseminating understanding of regenerative agriculture, horticulture, permaculture, ie the land, their work was exclusively carried out above ground, across which you could walk and talk about what was happening underneath you. What they needed, I reasoned, was a classroom that allowed people to experience the land from the inside. And so the hole. I know from personal experience how wonderful it is to be in a hole and thought yes, this is an experience I can contribute.

So that was the shining dream. The grubby reality, as we should expect, was a different matter, and thus the title for this blog post. The reason I am starting on day three is that I originally came up to do this residency months ago and promptly fell sick. I got a little work done, but eventually I packed it in after completing roughly two days of work. Now that I am returned, the structure for the project is in shambles. I’m not sure what I’m doing nor why, but that won’t stop me from doing it. In fact, the exact same thing happened the first time. I had some rather clever structure in place that would govern the limits of the work, setting it at five eight hour days a week for one month and this would determine the depth of the hole. This was meant to make some kind of comment on work itself or something. Yet, it almost immediately became impossible to complete because… I kept getting paid work in the city that meant I couldn’t complete the schedule I had set for myself. Oh Irony.

In the end, it greatly improved the work, discarding an arbitrary limit and reducing the work to what it was… work.

So I am starting on the third day and looking forward to whatever improvement this collapse of intention will deliver to the project. I have no idea what it is, nor whether it will come. I suppose I will just have to dig for it.

July 29, 2023

An Artist A Farmer and a Scientist Walk into a Bar

by Alex Wisser

From 2018 to 2020 I worked with my best mates at Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation (ksca) on a long term project engaging eight artists with farmers, scientists, aboriginal custodians, and rural stakeholders on a project that engaged with the efforts of farmers to transition from conventional, industrial methods of farming to more sustainable forms, often called regenerative farming. The project began with a stakeholder engagement in which ksca members met with members of the rural community of Bingara to discuss what we might do. The rather awkward title came out of our observation of the level of frustration and at times animosity that the Bingara folk expressed when talking about the scientists who could potentially validate their work. I had to admit that I was also naively surprised at the tension between those I thought would be natural allies in the endeavour to discover working methods for land management that would result in healthier landscapes and soil, increased resilience against drought, and a decreased resilience on the chemical inputs, monocultural planting and high soil disturbance practices that have seen a steady decline in the health of arable land across the globe.

There are many reasons for this dissonance, which we were to discover across the two year journey of the project but into this contradiction, we thought we could contribute as artists to bridge the failings of communication and the incommensurability of perspectives that seemed to be at play. It is important to remember that we also did not know what we were doing, which is at once a condition for making art and at the same time a liability when attempting to achieve tangible outcomes in the world. This was perhaps the contradiction that we brought to the situation, and one which I will hopefully grapple with for the rest of my life. What can art do to contribute to cultural change in the world as opposed to the cultural change we expect it to perform within the rarified crucible of the artworld?

It was clear that the farmers wanted us to perform some kind of communications function, to help them promote their cause. While this was not something that was off the table for us, the artists were resistant to being reduced to such a limited function. In fact, this is a common experience when engaging as artists with groups that will have little to no experience of art: their expectations are often constrained by their experience and understanding of art. There was also a desire that the project would produce some kind of lasting footprint, in the form of a public sculpture. This was nearly impossible as none of us make sculpture in the traditional sense. These misunderstandings are natural and can contribute meaningfully to the development of the project. My own work for AFS was to dig a three metre hole by hand at The Living Classroom, a facility run by the Bingara cohort to teach about regenerative and sustainable landcare. This work was an adaptation of a previous work of mine with the innovation that the hole I dug was meant to become a permanent classroom for a pedagogy that would take place in the earth itself, allowing demonstrations of soil composition and even (so I dreamed) root and soil ecology. More of that in later posts…

As for the KSCA crew, it was clear that we were interested in doing something more than serving the cause as glorified graphic designers and marketeers. In the end we conceived of the project as an attempt to generate a more fruitful conversations between farmers and scientist through the mediacy of the artist. I will be doing several posts about this project as it was a long one, and a lot happened so there is no need to jump to any conclusions as to the success or frustrations of this project here. Whether we managed to progress the relationship between farmers and scientists remains to be seen, but I can assure you the project was interesting, fun, challenging, and rewarding. To wet your appetite, check out the newspaper we produced as an outcome of the project